对妊娠24至34周有早产风险的孕妇给予产前糖皮质激素治疗是改善早产儿结局的最重要的产前治疗方法之一[1]。由于对晚期早产儿发病风险的低估,最初限制了对有晚期早产风险妇女使用产前糖皮质激素的建议[2]。2016年4月发表的晚期早产产前皮质类固醇试验(antenatal late preterm steroids,ALPS)表明,产前糖皮质激素的使用显著降低晚期早产儿呼吸系统并发症的发生率[3]。随后,美国妇产科医师学会和母胎医学学会修改了关于产前糖皮质激素的使用指导,将应用范围扩大到晚期早产[4-5]。然而,使用产前糖皮质激素治疗的晚期早产儿低血糖发生率较高,可能导致神经发育迟缓的远期风险,并且目前缺乏关于使用产前糖皮质激素对晚期早产儿长期影响的随访研究,因此,一些专家建议不要在晚期早产期间使用产前糖皮质激素[6-8]。

目前,中国没有关于晚期早产产前糖皮质激素使用推荐的相关指南或共识。鉴于现有的证据和各国相互矛盾的指南,目前尚不清楚中国晚期早产风险孕妇产前糖皮质激素的临床实践情况。因此,本文回顾性研究本院近6年有晚期早产风险的孕妇产前糖皮质激素的使用模式,并评估了产前糖皮质激素的给药时机及最佳给药时机的影响因素。

对象和方法

一、研究对象

纳入有晚期早产风险在妊娠34~36周接受产前糖皮质激素治疗的孕妇作为研究对象。排除外院转诊过来产前糖皮质激素用药记录不详的患者或在本院给予产前糖皮质激素治疗但未在本院分娩的孕妇。2016年1月至2022年12月本院共有658例孕妇在妊娠34~36周分娩,其中70例孕妇妊娠34周之前接受产前糖皮质激素治疗,119例孕妇在34~36周接受了产前糖皮质激素治疗,在37周前分娩。另有36例孕妇在妊娠34~36周接受了产前糖皮质激素治疗,但在足月分娩。最终共有155例孕妇被纳入该研究。孕妇年龄23~54岁。本研究经北京大学国际医院医学伦理委员会批准通过(2021-KY-0031-01)。

二、方法

1.资料的收集:从本院电子病历系统中提取出孕产妇病历资料。收集母亲年龄、产次、孕期并发症、分娩时的孕周和时间、产前糖皮质激素的给药指征、给药剂量及时间、给药时胎龄。

自发性早产[9]:妊娠未满37周自发性出现先兆早产、早产临产,继而发生早产分娩。医源性早产[9]:指由于母体或胎儿的健康原因不允许继续妊娠,在未达37周时采取引产或剖宫产终止妊娠。诊断标准参照《妇产科学》(第9版)[9]。根据给药指征对患者进行分组,分为自发性早产风险组(98名)、医源性早产风险组(57名)。其中自发性早产风险组孕妇年龄(31.8±4.3)岁,分娩时孕周35.1(34.7,37.9)周;医源性早产风险组年龄(32.2±3.9)岁,分娩时孕周35.1(34.7,35.7)周。

产前糖皮质激素给药方案是地塞米松每次6 mg,肌肉注射,每12 h给药1次,共4次[10]。最佳给药时机定义为距第1剂地塞米松给药与分娩之间的时间间隔为48 h~7 d[11]。如果该母亲接受了超过1个疗程的产前糖皮质激素,则根据最后疗程的应用时间对时机进行分类。

2.统计学处理:采用SPSS 23.0软件进行数据分析。符合正态分布的计量资料以均数±标准差![]() 表示,组间比较采用独立样本t检验;非正态分布的计量资料采用中位数及四分位数间距[M(P25,P75)]表示,组间比较采用非参数检验;计数资料以例数和百分率(%)表示,组间比较采用卡方检验或Fisher精确概率检验。采用多因素Logistic回归调整混杂因素,分析产前糖皮质激素最佳给药时机的影响因素。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

表示,组间比较采用独立样本t检验;非正态分布的计量资料采用中位数及四分位数间距[M(P25,P75)]表示,组间比较采用非参数检验;计数资料以例数和百分率(%)表示,组间比较采用卡方检验或Fisher精确概率检验。采用多因素Logistic回归调整混杂因素,分析产前糖皮质激素最佳给药时机的影响因素。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结 果

一、晚期早产风险的孕妇产前糖皮质激素给药情况

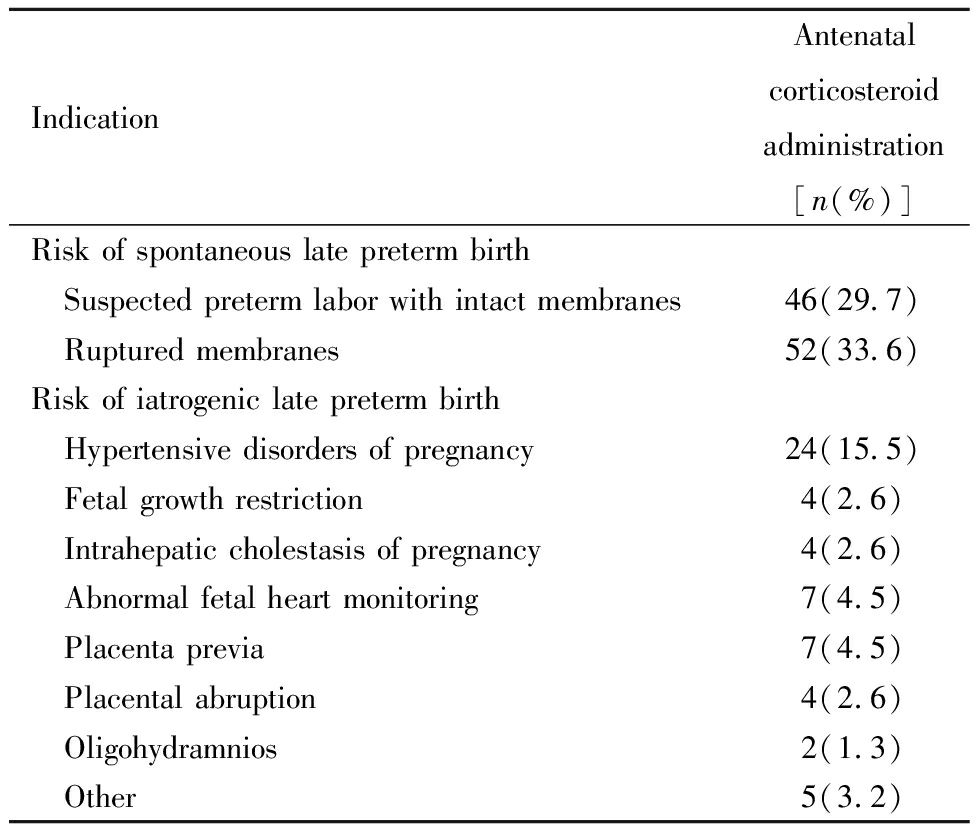

排除了在34周前使用产前糖皮质激素治疗的70例孕妇,共有588例孕妇在妊娠34~36周分娩,其中34周分娩的孕妇产前糖皮质激素使用率为70.8%(63/89),35周分娩的孕妇产前糖皮质激素使用率为27.3%(48/176),36周分娩的孕妇产前糖皮质激素使用率为2.5%(8/323)。34~36周使用产前糖皮质激素的孕妇早产分娩的共119例。另有36例孕妇因有晚期早产风险在妊娠34~36周接受产前糖皮质激素治疗,但并未发生早产,而在足月分娩(23.2%,36/155)。将这155例孕妇根据产前糖皮质激素的给药指征进行分组,其中自发性早产风险组98例(63.2%),医源性早产风险组57例(36.8%)。各组孕妇产前糖皮质激素给药的具体适应征分布见表1。

表1 155例晚期早产风险的孕妇产前糖皮质激素给药适应征

Table 1 Indications for antenatal corticosteroid administration among 155 pregnant women at risk for late preterm delivery

IndicationAntenatal corticosteroid administration[n(%)]Risk of spontaneous late preterm birth Suspected preterm labor with intact membranes46(29.7) Ruptured membranes52(33.6)Risk of iatrogenic late preterm birth Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy24(15.5) Fetal growth restriction4(2.6) Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy4(2.6) Abnormal fetal heart monitoring7(4.5) Placenta previa7(4.5) Placental abruption4(2.6) Oligohydramnios2(1.3) Other5(3.2)

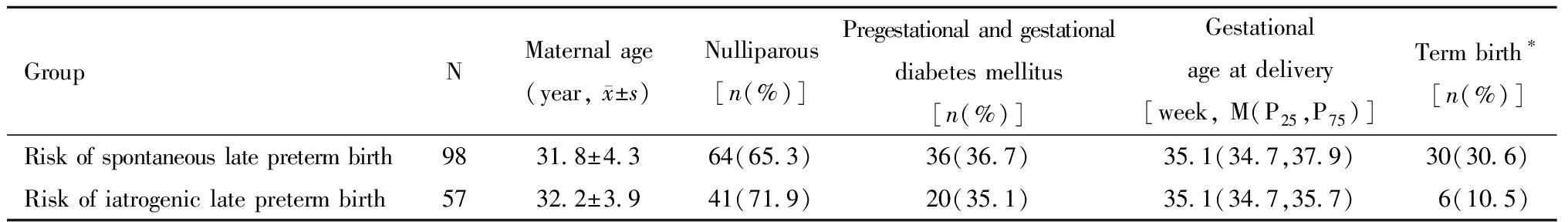

二、自发性早产风险组与医源性早产风险组孕妇特征的比较

与自发性早产风险的孕妇相比,医源性早产风险的孕妇在年龄、产次及妊娠前或妊娠期糖尿病的发生率方面均无显著差异(P>0.05)。两组孕妇使用产前糖皮质激素后分娩时的胎龄无显著差异,但自发性早产组的孕妇使用产前糖皮质激素后发生足月分娩的比率显著高于医源性早产组(P=0.004)。见表2。

表2 自发早产风险组和医源性早产风险组母亲特征的比较

Table 2 Comparison of maternal characteristics between study groups

GroupNMaternal age(year, x±s)Nulliparous[n(%)]Pregestational and gestationaldiabetes mellitus[n(%)]Gestational age at delivery[week, M(P25,P75)]Term birth∗[n(%)]Risk of spontaneous late preterm birth9831.8±4.364(65.3)36(36.7)35.1(34.7,37.9)30(30.6)Risk of iatrogenic late preterm birth5732.2±3.941(71.9)20(35.1)35.1(34.7,35.7)6(10.5)

Compared with the risk of iatrogenic late preterm group,*P<0.05

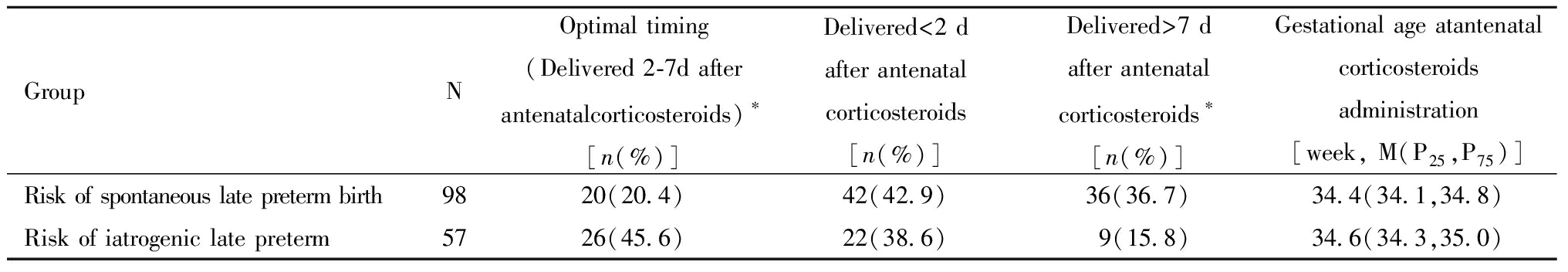

三、自发性早产风险组与医源性早产风险组孕妇产前糖皮质激素给药时机的比较

对于有早产风险在妊娠34~36周接受产前糖皮质激素治疗的孕妇,最优给药时机(给药距分娩间隔2~7 d)的比例为29.7%(46/155),其中医源性早产风险组孕妇最优给药时机的比例为45.6%(26/57),显著高于自发性早产风险组孕妇最优给药时机的比例为20.4%(20/98)(P=0.001)。与医源性早产风险组相比,产前糖皮质激素给药距分娩间隔>7 d在自发性早产风险组更常见(P=0.006)。但两组间孕妇在产前糖皮质激素给药距分娩<2 d的比例无显著差异(P=0.603)。两组孕妇接受产前糖皮质激素给药时的胎龄亦无显著差异(P=0.122)。见表3。

表3 自发性早产风险组和医源性早产风险组产前糖皮质激素给药时机的比较[例(%)]

Table 3 Comparison of timing of antenatal corticosteroids administration between study groups

GroupNOptimal timing (Delivered 2-7d after antenatalcorticosteroids)∗[n(%)]Delivered<2 d after antenatal corticosteroids[n(%)]Delivered>7 dafter antenatal corticosteroids∗[n(%)]Gestational age atantenatalcorticosteroids administration[week, M(P25,P75)]Risk of spontaneous late preterm birth9820(20.4)42(42.9)36(36.7)34.4(34.1,34.8)Risk of iatrogenic late preterm5726(45.6)22(38.6)9(15.8)34.6(34.3,35.0)

Compared with the risk of iatrogenic late preterm group,*P<0.05

四、孕妇在最优给药时机接受产前糖皮质激素治疗的影响因素

通过Logistic回归分析,调整了母亲年龄、产次、产前糖皮质激素给药时胎龄、合并妊娠前或妊娠期糖尿病的比例影响后,发现医源性早产风险组的孕妇在最优给药时机接受产前糖皮质激素的机会是自发性早产的8.68倍(95% CI :2.69~28.02),胎膜早破的孕妇在最优给药时机接受产前糖皮质激素治疗的机会是无胎膜早破孕妇的4.09倍(95% CI:1.24~13.45)。而产前糖皮质激素给药时胎龄与最优给药时机没有相关性(P=0.32)。见表4。

表4 多因素logistic回归评估产前糖皮质激素最佳给药时机的影响因素

Table 4 Multivariable logistic regression to evaluate factors associated with optimal timing of antenatal corticosteroids administration

FactorsaOR95%CIPMaternal age0.990.89-1.110.99Nulliparous1.710.68-4.320.26Pregestational and gestational diabetes mellitus1.110.51-2.430.80Ruptured membranes4.091.24-13.450.02Gestational age at antenatal corticosteroids administration0.670.31-1.460.32Indications for antenatal corticosteroids administrationIatrogenic late preterm birth8.682.69-28.02<0.001Spontaneous late preterm birthReference——

讨 论

美国最近的一项研究报告称,ALPS研究的发表与美国晚期早产儿使用产前糖皮质激素的比率增加有关[12]。据报道,35周分娩的妇女使用产前糖皮质激素的比率从2016年的14%急剧增加到2020年的27%,而36周分娩的妇女使用产前糖皮质激素的比率从2016年的7%增加到2020年的16%[13]。在本研究中,35周早产儿的母亲产前糖皮质激素使用率为27.3%,与美国2020年的使用率相似。但36周早产儿的母亲产前糖皮质激素使用率仅为2.5%,远远低于美国。这种比例的差异与两国指南和临床实践不一致有关[4,10]。

大部分支持在晚期早产使用产前糖皮质激素的证据来自ALPS试验[3],但最近对产科医生的调查中发现,大部分产科医生在ALPS纳入标准之外对晚期早产使用产前糖皮质激素,包括妊娠期糖尿病妇女和多胎妊娠妇女等[14]。这可能导致新生儿不能获得ALPS试验中相似的收益。在本院的临床实践中,患有妊娠前或妊娠期糖尿病的孕妇也有相当一部分使用产前糖皮质激素。前期研究结果显示,使用产前糖皮质激素并未显著降低晚期早产儿呼吸系统疾病的发生率及呼吸支持的使用[15],原因可能与之有关。

产前糖皮质激素的治疗效果通常被认为在给药后48 h~7 d内疗效最大,并可能在7 d后消失[11,16-17]。然而,产前糖皮质激素的给药时机仍不理想,已在妊娠<34周有早产风险的妇女中得到证实[18-20]。只有15%至40%接受产前糖皮质激素治疗的妇女在分娩前7 d的最佳窗口内接受治疗[21]。一项对于晚期早产产前糖皮质激素给药时机的研究显示,产前糖皮质激素给药后2~7 d内分娩的可能性也很低,只有13.3%在该时间间隔内分娩[22]。在本研究中,晚期早产风险的孕妇接受产前糖皮质激素治疗后2~7 d分娩的可能性为29.7%,表明晚期早产产前糖皮质激素给药时机与<34周的早产相似,最佳给药时机的可能性均较低。有研究证实,产前糖皮质激素给药的时机因早产原因而异[23-24]。在本研究中,晚期早产原因为医源性的孕妇最佳给药时机的可能性显著高于早产原因为自发性早产的妇女,表明在医源性晚期早产的妇女中,在期望的最佳给药时机期间分娩更为常见。这与Gulersen等[22]的研究一致。先前有研究报道[18,23],胎膜早破的早产儿母亲更有可能在最佳给药时机接受产前糖皮质激素应用,这在本研究也得到了证实。表明产科医师更擅长依据实际情况预测胎膜早破孕妇的分娩时机,很可能是由于存在对胎膜早破此类患者的具体的分娩的建议[25]。Gulersen等[22]的研究发现,在晚期早产期间,皮质类固醇给药时胎龄越大,最佳时机的可能性越高。但在本研究中给药时胎龄与最佳给药时机并没有相关性。

产前糖皮质激素给药时机不仅是疗效的关键,也是安全性的关键。越来越多的证据表明,在子宫内暴露于产前糖皮质激素的足月婴儿出现短期和长期不良后果的风险增加,即使在任何胎龄时只进行一次产前治疗[26-27]。在芬兰的研究中,宫内受到皮质类固醇暴露后,足月出生的儿童患精神和行为障碍的风险要大得多,而早产儿的差异没有统计学意义[27]。由于晚期早产更接近足月,可能导致给予产前糖皮质激素治疗后的孕妇更多发生在足月分娩。在ALPS试验中,接受产前糖皮质激素治疗的孕妇有16.4%在足月分娩[3]。另外一项研究中,晚期早产期间暴露于产前糖皮质激素的孕妇有24.6%在足月后分娩[22]。在本研究中,晚期早产期间暴露于产前糖皮质激素的孕妇足月分娩的发生率为23.2%。尽管产前糖皮质激素对足月出生儿童的不良神经发育影响的深度和广度仍不清楚,但继续忽视潜在医源性损害的迅速积累的证据是不合理的。

本研究有两个优势。本研究调查了有晚期早产风险的孕妇产前糖皮质激素给药后在假定的最佳给药时机内分娩的可能性,并根据给药适应症进行了分层,以比较自发性晚期早产风险的孕妇与医源性晚期早产风险的孕妇产前糖皮质激素给药时机的差异。然而,本研究的局限性在于样本量小,对于应用于产前糖皮质激素给药的医学适应症,如胎儿生长受限、羊水过少、胎盘异常和胎儿状态不稳定等相对罕见,限制了本研究在回归分析中评估每个适应症产前糖皮质激素最佳给药时机的可能性。

综上所述,本研究发现,有晚期早产风险的孕妇在接受产前糖皮质激素后2~7 d分娩的可能性很低。与自发性期早产风险的妇女相比,医源性晚期早产风险的妇女在最佳给药时机期间分娩的可能性更高。此外,胎膜早破的晚期早产风险的孕妇更可能在最佳给药时机得到产前糖皮质激素治疗。为了使产前糖皮质激素发挥最大疗效,且避免产生不良影响,产科应对产前糖皮质激素这一措施进行质量改进,质量标准应侧重于在最佳疗效窗口期内给药,而不是对有早产风险的孕妇普遍给药。要注重评估有晚期早产风险的孕妇在晚期早产期间给予产前糖皮质激素后孕妇足月分娩的发生率,理论上理想的比率为0。通过这些新的度量标准,结束“以防万一”的产前糖皮质激素管理实践。

1 McGoldrick E,Stewart F,Parker R,et al.Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth.Cochrane Database Syst Rev,2020,12:CD004454.

2 Escobar GJ,Clark RH,Greene JD.Short-term outcomes of infants born at 35 and 36 weeks gestation:we need to ask more questions.Semin Perinatol,2006,30:28-33.

3 Gyamfi-Bannerman C,Thom EA,Blackwell SC,et al.Antenatal Betamethasone for Women at Risk for Late Preterm Delivery.N Engl J Med,2016,374:1311-1320.

4 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists′ Committee on Obstetric Practice; Society for Maternal- Fetal Medicine.Committee Opinion No.677:Antenatal Corticosteroid Therapy for Fetal Maturation.Obstet Gynecol,2016,128:e187-194.

5 Implementation of the use of antenatal corticosteroids in the late preterm birth period in women at risk for preterm delivery.Am J Obstet Gynecol,2016,215:B13-15.

6 Deshmukh M,Patole S.Antenatal corticosteroids for impending late preterm (34-36+6 weeks) deliveries-A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs.PLoS One,2021,16:e0248774.

7 DeMauro SB.Antenatal Corticosteroids-Too Much of a Good Thing.JAMA,2020,323:1910-1912.

8 Jobe AH.Antenatal Corticosteroids-A Concern for Lifelong Outcomes.J Pediatr,2020,217:184-188.

9 谢幸,孔北华,段涛.妇产科学.第9版.北京:人民卫生出版社,2018:95-140.

10 中华医学会妇产科学分会产科学组.早产临床诊断与治疗指南.中华妇产科杂志,2014,49:481-485.

11 Committee Opinion No.713:Antenatal Corticosteroid Therapy for Fetal Maturation.Obstet Gynecol,2017,130:e102-e109.

12 Kearsey E,Been JV,Souter VL,et al.The impact of the Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids trial on the administration of antenatal corticosteroids.Am J Obstet Gynecol,2022,227:280.e1-280.e15.

13 Razaz N,Allen VM,Fahey J,et al.Antenatal Corticosteroid Prophylaxis at Late Preterm Gestation:Clinical Guidelines Versus Clinical Practice.J Obstet Gynaecol Can,2023,45:319-326.

14 Battarbee AN,Clapp MA,Boggess KA,et al.Practice Variation in Antenatal Steroid Administration for Anticipated Late Preterm Birth:A Physician Survey.Am J Perinatol,2019,36:200-204.

15 王慧,曹丽芳,张雪峰.产前糖皮质激素对晚期早产儿呼吸系统疾病的影响.临床儿科杂志,2021,39:410-414.

16 Yasuhi I,Myoga M,Suga S,et al.Influence of the interval between antenatal corticosteroid therapy and delivery on respiratory distress syndrome.J Obstet Gynaecol Res,2017,43:486-491.

17 Battarbee AN,Ros ST,Esplin MS,et al.Optimal timing of antenatal corticosteroid administration and preterm neonatal and early childhood outcomes.Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM,2020,2:100077.

18 Adams TM,Kinzler WL,Chavez MR,et al.Practice patterns in the timing of antenatal corticosteroids for fetal lung maturity.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med,2015,28:1598-1601.

19 Adams TM,Kinzler WL,Chavez MR,et al.The timing of administration of antenatal corticosteroids in women with indicated preterm birth.Am J Obstet Gynecol,2015,212:645.e1-4.

20 Levin HI,Ananth CV,Benjamin-Boamah C,et al.Clinical indication and timing of antenatal corticosteroid administration at a singlecentre.BJOG,2016,123:409-414.

21 Vidaeff AC,Belfort MA,Kemp MW,et al.Updating the balance between benefits and harms of antenatal corticosteroids.Am J Obstet Gynecol,2023,228:129-132.

22 Gulersen M,Gyamfi-Bannerman C,Greenman M,et al.Practice patterns in the administration of late preterm antenatal corticosteroids.AJOG Glob Rep,2021,1:100014.

23 Hannah DM,Taboada CD,Tressler TB,et al.Analysis of clinical diagnosis for all patients receiving antenatal betamethasone in a community hospital.J Neonatal Perinatal Med,2018,11:295-303.

24 王慧,曹丽芳,张雪峰.产前糖皮质激素应用时机及与早产原因的关系.中国生育健康杂志,2022,33:362-365.

25 Practice Bulletin No.172:Premature Rupture of Membranes.Obstet Gynecol,2016,128:e165-177.

26 McKinzie AH,Yang Z,Teal E,et al.Are newborn outcomes different for term babies who were exposed to antenatal corticosteroids.Am JObstet Gynecol,2021,225:536.e1-536.e7.

27 Räikkönen K,Gissler M,Kajantie E.Associations Between Maternal Antenatal Corticosteroid Treatment and Mental and Behavioral Disorders in Children.JAMA,2020,323:1924-1933.