·综述·

孕期焦虑评估方式对不良出生结局的影响

叶云 邵珊珊

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(81803248)

作者单位:230032 合肥,安徽医科大学公共卫生学院儿少卫生与妇幼保健学系,出生人口健康教育部重点实验室,人口健康与优生安徽省重点实验室

通讯作者:邵珊珊(shaoshsh@126.com)

【摘要】 孕期焦虑是孕妇最常见的心理问题。数十年来,大量研究包括meta分析报道了孕期焦虑与不良出生结局的关联性,然而至今并未取得一致性结论。考虑到孕期焦虑有其时间和内容特殊性,本文对近二十年来有关妊娠相关焦虑与不良出生结局的流行病学研究进行了综述,发现与孕期一般焦虑相比,妊娠相关焦虑与不良出生结局的关联性更为稳定。未来的科学研究与临床工作需对妊娠相关焦虑提高重视,以尽早预防不良出生结局的发生。

【关键词】 妊娠相关焦虑; 孕期焦虑; 不良出生结局; 评估方式

焦虑障碍是一组以焦虑和恐惧感为特征的精神障碍,表现为对某些事件的过度担忧或高度持续的恐惧反应。据报道,大约13.2%的孕妇患有焦虑障碍[1],遭受焦虑情绪困扰的孕妇比例更大。作为产前应激的一种常见类型,孕期焦虑会通过损害神经发育、神经认知功能、大脑加工、功能性和结构性脑区链接、下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺轴和自主神经系统,影响后代的发育和远期健康[2]。截至目前为止,已有大量研究关注了孕期焦虑与早产、低出生体重等不良出生结局的关联性,但并未得到一致性结论。由于不良出生结局会给母婴健康带来严重影响[3-4],阐明孕期焦虑与不良出生结局的确切关系十分必要。本文不良出生结局包括早产、低出生体重和小于胎龄儿。根据儿科学的定义,早产是指妊娠满28周至不足37周之间分娩的新生儿。低出生体重儿是指婴儿出生体重<2 500 g。而小于胎龄儿是指婴儿的出生体重低于同胎龄平均体重第10个百分位数[5]。

现有研究对孕期焦虑的评估方式尚不统一。一部分研究使用的是诸如DSM-IV临床定式访谈(Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders,SCID-IV)、状态-特质焦虑量表(State-Trait Anxiety Inventory,STAI)、汉密尔顿焦虑量表(Hamilton Anxiety Scale,HAMA)等通用于任何时期焦虑评估的量表[6-8],一部分研究使用的是自编的妊娠相关焦虑量表(Pregnancy-related Anxiety Questionnaire,PRAQ)[9-11]。由于后者专门评估孕期妊娠相关事件(如对胎儿健康、胎儿生命、自身健康/外表、分娩疼痛/安全以及未来育儿技能、经济问题等)引起的焦虑情绪,称为妊娠相关焦虑(pregnancy-related anxiety)[12],而前者称为孕期一般焦虑(general anxiety)。因评估方式不同导致研究对象错误分类,很可能是造成研究间孕期焦虑与不良出生结局关联性不一致的原因。

为探讨孕期焦虑评估方式对孕期焦虑与不良出生结局关联性的影响,作者基于中国知网、万方、PubMed、Web of Science数据库,以“孕期焦虑(pregnancy anxiety)、妊娠特有焦虑(pregnancy-specific anxiety)、妊娠相关焦虑(pregnancy-related anxiety)、不良出生结局(adverse birth outcomes)、早产(premature birth)、低出生体重(low birth weight)、小于胎龄儿(small gestational age)”为检索词,检索了自2001年1月1日到2019年6月30日发表的孕期焦虑与不良出生结局的文献,纳入标准为样本量大于100的病例对照或队列研究,重点整理和分析不同评估方式下孕期焦虑与不良出生结局的关联性。

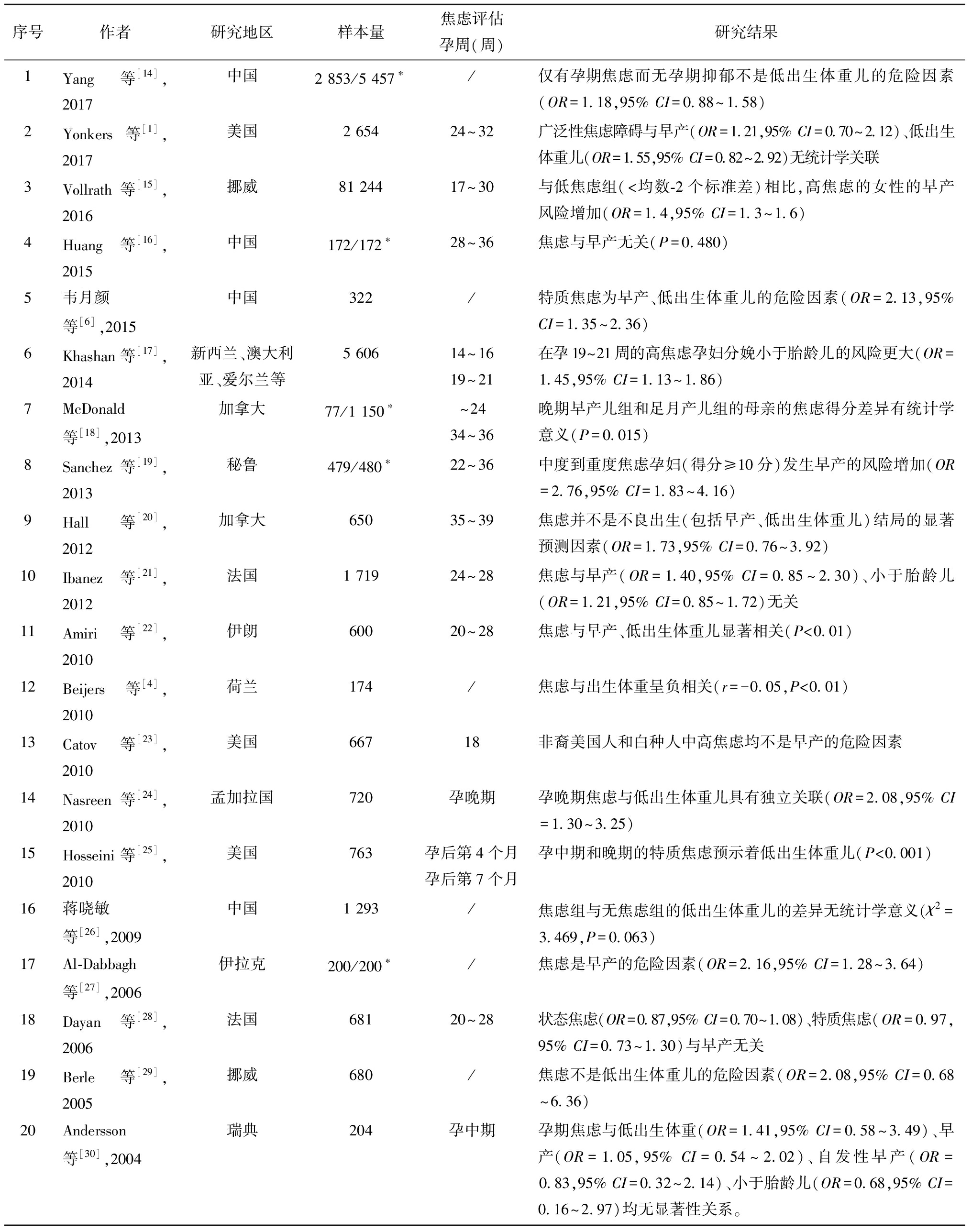

一、孕期一般焦虑与不良出生结局的关联性

如表1所示,根据纳入标准,本文检索到的20篇有关孕期一般焦虑与不良出生结局关联性的文献。支持和不支持孕期一般焦虑与早产、低出生体重、小于胎龄儿显著相关的文献数量分别为6篇vs.7篇、4篇vs.7篇、1篇vs.3篇。根据研究设计、样本量、数据完整性等指标对支持与不支持的文献进行研究质量评定[13],发现并无显著差异。使用通用型量表评估孕期焦虑,孕期焦虑与不良出生结局的关联性存在明显不一致性。

表1 2001年至今样本量大于100的孕期一般焦虑与不良出生结局的关联研究汇总

序号作者研究地区样本量焦虑评估孕周(周)研究结果1Yang等[14],2017中国2 853/5 457∗/仅有孕期焦虑而无孕期抑郁不是低出生体重儿的危险因素(OR=1.18,95% CI=0.88~1.58)2Yonkers等[1],2017美国2 65424~32广泛性焦虑障碍与早产(OR=1.21,95% CI=0.70~2.12)、低出生体重儿(OR=1.55,95% CI=0.82~2.92)无统计学关联3Vollrath等[15],2016挪威81 24417~30 与低焦虑组(<均数-2个标准差)相比,高焦虑的女性的早产风险增加(OR=1.4,95% CI=1.3~1.6)4Huang等[16],2015中国172/172∗28~36 焦虑与早产无关(P=0.480)5韦月颜等[6],2015中国322/特质焦虑为早产、低出生体重儿的危险因素(OR=2.13,95% CI=1.35~2.36)6Khashan等[17],2014新西兰、澳大利亚、爱尔兰等5 60614~1619~21 在孕19~21周的高焦虑孕妇分娩小于胎龄儿的风险更大(OR=1.45,95% CI=1.13~1.86)7McDonald等[18],2013加拿大77/1 150∗~2434~36晚期早产儿组和足月产儿组的母亲的焦虑得分差异有统计学意义(P=0.015)8Sanchez等[19],2013秘鲁479/480∗22~36 中度到重度焦虑孕妇(得分≥10分)发生早产的风险增加(OR=2.76,95% CI=1.83~4.16)9Hall等[20],2012加拿大65035~39 焦虑并不是不良出生(包括早产、低出生体重儿)结局的显著预测因素(OR=1.73,95% CI=0.76~3.92)10Ibanez等[21],2012法国1 71924~28 焦虑与早产(OR=1.40,95% CI=0.85~2.30)、小于胎龄儿(OR=1.21,95% CI=0.85~1.72)无关11Amiri等[22],2010伊朗60020~28 焦虑与早产、低出生体重儿显著相关(P<0.01)12Beijers等[4],2010荷兰174/焦虑与出生体重呈负相关(r=-0.05,P<0.01)13Catov等[23],2010美国66718非裔美国人和白种人中高焦虑均不是早产的危险因素14Nasreen等[24],2010孟加拉国720孕晚期孕晚期焦虑与低出生体重儿具有独立关联(OR=2.08,95% CI=1.30~3.25)15Hosseini等[25],2010美国763孕后第4个月孕后第7个月孕中期和晚期的特质焦虑预示着低出生体重儿(P<0.001)16蒋晓敏等[26],2009中国1 293/焦虑组与无焦虑组的低出生体重儿的差异无统计学意义(χ2 =3.469,P=0.063)17Al-Dabbagh等[27],2006伊拉克200/200∗/焦虑是早产的危险因素(OR=2.16,95% CI=1.28~3.64)18Dayan等[28],2006法国68120~28 状态焦虑(OR=0.87,95% CI=0.70~1.08)、特质焦虑(OR=0.97,95% CI=0.73~1.30)与早产无关19Berle等[29],2005挪威680/焦虑不是低出生体重儿的危险因素(OR=2.08,95% CI=0.68~6.36)20Andersson等[30],2004瑞典204孕中期孕期焦虑与低出生体重(OR=1.41,95% CI=0.58~3.49)、早产(OR=1.05,95% CI=0.54~2.02)、自发性早产(OR= 0.83,95% CI=0.32~2.14)、小于胎龄儿(OR=0.68,95% CI=0.16~2.97)均无显著性关系。

*标注的研究是病例对照研究(早产儿数/足月产儿数),其余均为队列研究。

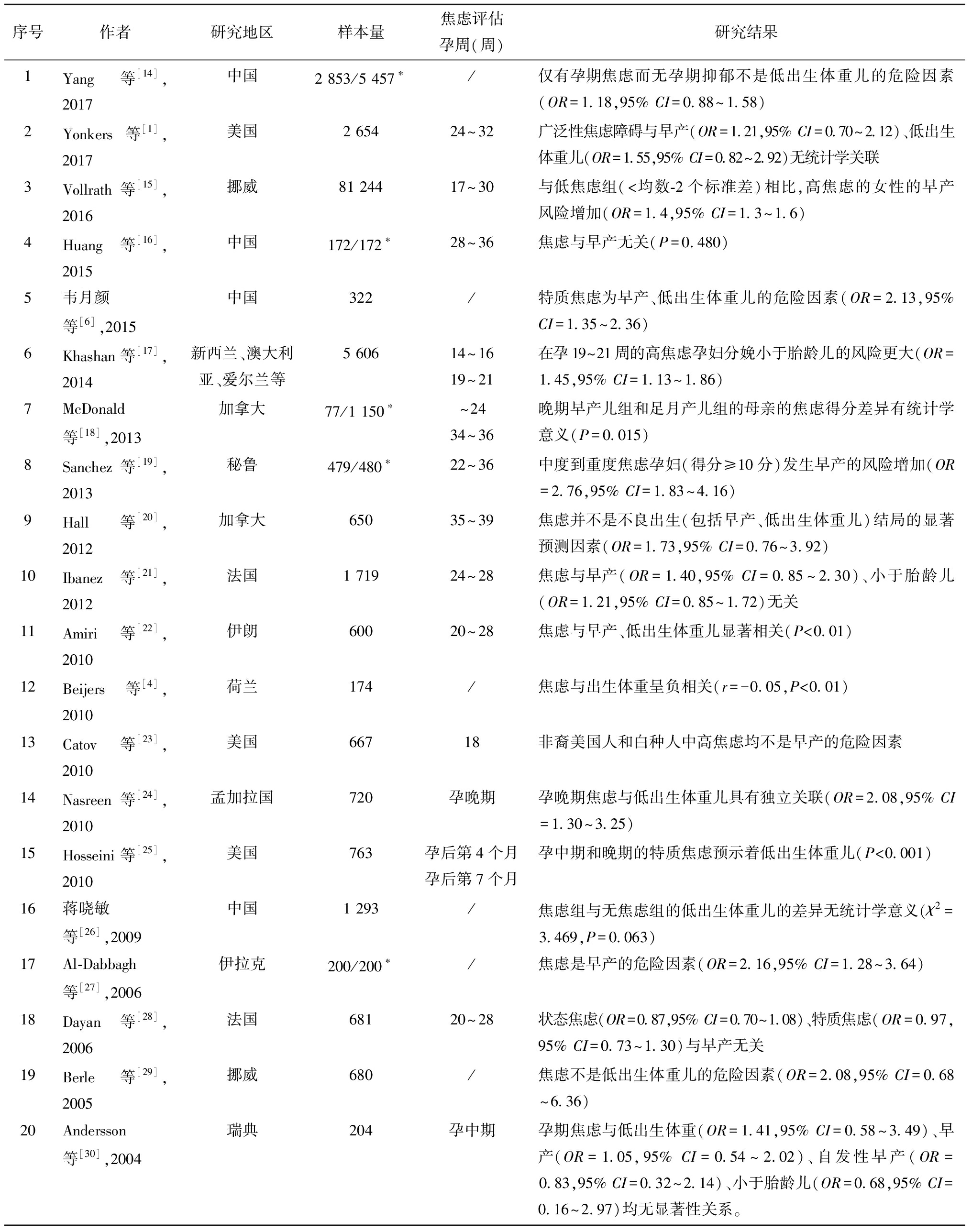

二、孕期妊娠相关焦虑与不良出生结局的关联性

如表2所示,根据纳入标准,本文检索到13篇孕期妊娠相关焦虑与不良出生结局关联性的文献。从整体上看,除Loomans等[31]的研究外,其他12项研究均提示妊娠相关焦虑与早产或低出生体重或小于胎龄儿发生风险的增加显著相关。使用妊娠相关焦虑量表评估孕期焦虑,孕期焦虑与不良出生结局的关联性基本一致。

表2 2001年至今样本量大于100的孕期妊娠相关焦虑与不良出生结局的关联研究汇总

序号作者研究地区样本量评估孕周(周)研究结果1Ramos等[9],2019美国(拉丁白人)10719、25 、31 孕31周的妊娠相关焦虑得分每增加一个标准差,孕龄减少3.4d(P=0.002),孕19周的妊娠相关焦虑得分每增加一个标准差,孕龄减少2.6d(P=0.017)。2Khalesi等[10],2018伊朗20820~2830~38 孕晚期(而不是孕中期)妊娠相关焦虑与早产相关(P<0.01)。3来亚平等[11],2018中国3 040孕中期孕晚期孕中晚期均存在妊娠相关焦虑为小于胎龄儿的危险因素(OR=1.39,95% CI=1.04~1.87)。4Loomans等[31],2013荷兰7 74014~18 相比于“低抑郁低焦虑且适度工作压力”组,“低焦虑低抑郁且有妊娠相关焦虑”组的早产、出生体重、胎龄无显著性变化。5Fleuriet等[32],2015墨西哥631孕期高妊娠相关焦虑的孕妇分娩正常体重儿或高体重儿的风险是低妊娠相关焦虑孕妇的0.89倍(OR=0.89,95% CI=0.81~0.97),而自我感知的社会压力与出生体重无关。6Rauchfuss等[33],2011德国58913~14 妊娠相关焦虑与早产呈正相关(OR=1.44,95% CI=1.02~2.05)。7Beijers等[4],2010荷兰174孕期妊娠相关焦虑中的害怕分娩(r=-0.10,P < 0.01)、害怕分娩残疾孩子(r=-0.02;P < 0.01)与出生体重成负相关。8Ghosh等[34],2010美国1 027/1 282∗孕期对正常分娩无信心(OR=1.57,95% CI=1.17~2.12)和担心胎儿健康(OR=1.67,95% CI=1.30~2.14)会增加自发性早产的风险,但是孕期生活事件与早产无关。9Kramer等[35],2009加拿大5 09224~26 妊娠相关焦虑为早产的危险因素(OR=1.80,95% CI=1.30~2.40),但是孕期负性生活事件和自我感知压力与自发性早产无关。10Orr等[36],2007美国1 820第一次产检妊娠相关焦虑得分为6分(最高得分)的孕妇的早产风险几乎为得分<4分的孕妇的3倍(OR=2.73,95% CI=1.03~7.23)。11Mancuso等[37],2004美国28218~2028~30 孕28~30周(而不是孕18~20周)妊娠相关焦虑与早产相关(r=-0.19,P<0.01)。12Dole等[38],2004美国1 89824~29 非裔美国人中妊娠相关焦虑是早产的危险因素(RR=2.0,95% CI=1.3~3.2),白人中妊娠相关焦虑是早产的危险因素(RR=1.6,95% CI=1.1~2.3)。13Dole等[39],2003美国1 96224~29 高水平妊娠相关焦虑是早产的危险因素(RR=2.0,95% CI=1.4~1.8),对自发性早产的影响更为大(RR=2.5,95% CI=1.6~3.9),但是抑郁与早产无关,孕期生活事件与早产的关系不稳定,取决于生活事件的评定方法。

*Ghosh等(2010)是病例对照研究(早产儿数/足月产儿数);其余均为队列研究。

三、讨论

本篇综述提示,孕期焦虑的评估方式会影响孕期焦虑与不良出生结局的关联性。相比于孕期一般焦虑,妊娠相关焦虑对不良出生结局(特别是早产)有更加稳定的预测作用。这一点最早在Littleton等[3]的Meta分析中就有端倪露出,文章发现虽然总体上看孕期焦虑与不良出生结局无关,但是孕期妊娠相关焦虑与出生胎龄有着微弱的关联。13篇孕期妊娠相关焦虑与不良出生结局关联性的文献中,仅仅Loomans等[31]的研究提示妊娠相关焦虑与不良出生结局无关,而Loomans等[31]的这项研究采用了因子分析法对研究对象进行分组,方法本身存在15.2%的误分类风险,此外由于对照组“低抑郁低焦虑且适度工作压力”的妊娠相关焦虑情况不详,其研究结果并不能说明妊娠相关焦虑是否为不良出生结局的危险因素。

通用型情绪评估量表与妊娠相关焦虑量表评估的结果存在异质性。Huizink等[40]的研究发现,STAI量表和爱丁堡产后抑郁量表评估的孕早和孕中的一般焦虑和抑郁只解释了同时期妊娠相关焦虑8%~27%的变异性,而孕晚期的一般焦虑或抑郁和同时期妊娠相关焦虑毫无关系。随后,一项研究通过因子分析进一步证实了妊娠相关焦虑评估量表与流调中心抑郁量表在结构上是独立的[36]。可见,STAI等通用型焦虑评估量表或许并不适用于孕期焦虑的评估。

SCID-IV等临床用诊断性访谈以6个月及以上的持续时间作为焦虑障碍的诊断标准可能也不适用于孕期焦虑的评估[41]。因为妊娠相关焦虑可以是孕前焦虑受新应激(指怀孕)情境下的特有表现,但也可能是怀孕后才出现的。对于相对较短的40周孕期,6个月及以上的持续时间作为诊断标准不利于孕期焦虑的早期预防,如果真如本文所示,妊娠相关焦虑与不良出生结局之间显著相关,6个月的诊断时间将延误治疗。

本篇综述不足之处在于:第一,没有考虑一般焦虑研究和妊娠相关焦虑研究中孕产妇的年龄和躯体状况差异;第二,相对于早产,妊娠相关焦虑与低出生体重、小于胎龄儿等其他不良出生结局的研究还很少,需要更多的研究来确定妊娠相关焦虑的危害范围和程度。由于妊娠相关焦虑在内容和时间上存在特殊性,现有评估方法(包括现有专门用于评估妊娠相关焦虑的量表)不足以对其进行精确评估,开发并使用相关评估工具和诊断标准尤为迫切。

参考文献

1 Yonkers KA,Gilstad-Hayden K,Forray A,et al.Association of Panic Disorder,Generalized Anxiety Disorder,and Benzodiazepine Treatment During Pregnancy With Risk of Adverse Birth Outcomes.JAMA Psychiatry,2017,74:1145-1152.

2 Van den Bergh BRH,van den Heuvel MI,Lahti M,et al.Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health:The influence of maternal stress in pregnancy.Neurosci Biobehav Rev,2020,117:26-64.

3 Littleton HL,Breitkopf CR,Berenson AB.Correlates of anxiety symptoms during pregnancy and association with perinatal outcomes:a meta-analysis.Am J Obstet Gynecol,2007,196:424-432.

4 Beijers R,Jansen J,Riksen-Walraven M,et al.Maternal prenatal anxiety and stress predict infant illnesses and health complaints.Pediatrics,2010,126:e401-409.

5 王卫平.儿科学.第8版.北京:人民卫生出版社,2013:93-94.

6 韦月颜,陶真兰,程虹,等.孕妇焦虑和抑郁情绪对妊娠结局的影响.职业与健康,2015,31:1213-1216.

7 Uguz F,Sahingoz M,Sonmez EO,et al.The effects of maternal major depression,generalized anxiety disorder,and panic disorder on birth weight and gestational age:a comparative study.J Psychosom Res,2013,75:87-89.

8 Maina G,Saracco P,Giolito MR,et al.Impact of maternal psychological distress on fetal weight,prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation.J Affect Disord,2008,111:214-220.

9 Ramos IF,Guardino CM,Mansolf M,et al.Pregnancy anxiety predicts shorter gestation in Latina and non-Latina white women:The role of placental corticotrophin-releasing hormone.Psychoneuroendocrinology,2019,99:166-173.

10 Khalesi ZB,Bokaie M.The association between pregnancy-specific anxiety and preterm birth:a cohort study.Afr Health Sci,2018,18:569-575.

11 来亚平,严双琴,黄锟,等.妊娠相关焦虑与小于胎龄儿的关联研究.中华流行病学杂志,2018,39:1329-1332.

12 Bayrampour H,Ali E,McNeil DA,et al.Pregnancy-related anxiety:A concept analysis.Int J Nurs Stud,2016,55:115-130.

13 Hughes K,Bellis MA,Jones L,et al.Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities:a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies.Lancet,2012,379:1621-1629.

14 Yang S,Yang R,Liang S,et al.Symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy and their association with low birth weight in Chinese women:a nested case control study.Arch Womens Ment Health,2017,20:283-290.

15 Vollrath ME,Sengpiel V,Landolt MA,et al.Is maternal trait anxiety a risk factor for late preterm and early term deliveries?.BMC Pregnancy Childbirth,2016,16:286.

16 Huang A,Jin X,Liu X,et al.A matched case-control study of preterm birth in one hospital in Beijing,China.Reprod Health,2015,12:1.

17 Khashan AS,Everard C,Mccowan LM,et al.Second-trimester maternal distress increases the risk of small for gestational age.Psychol Med,2014,44:2799-2810.

18 Mcdonald SW,Benzies KM,Gallant JE,et al.A comparison between late preterm and term infants on breastfeeding and maternal mental health.Matern Child Health J,2013,17:1468-1477.

19 Sanchez SE,Puente GC,Atencio G,et al.Risk of spontaneous preterm birth in relation to maternal depressive,anxiety,and stress symptoms.J Reprod Med,2013,58:25.

20 Hall WA,Stoll K,Hutton EK,et al.A prospective study of effects of psychological factors and sleep on obstetric interventions,mode of birth,and neonatal outcomes among low-risk British Columbian women.BMC Pregnancy Childbirth,2012,12:78.

21 Ibanez G,Charles MA,Forhan A,et al.Depression and anxiety in women during pregnancy and neonatal outcome:data from the EDEN mother-child cohort.Early Hum Dev,2012,88:643-649.

22 Amiri FN,Mohamadpour RA,Salmalian H,et al.The association between prenatal anxiety and spontaneous preterm birth and low birth weight.Iran Red Crescent Me,2010,12:650-654.

23 Catov JM,Abatemarco DJ,Markovic N,et al.Anxiety and Optimism Associated with Gestational Age at Birth and Fetal Growth.Matern Child Health J,2010,14:758-764.

24 Nasreen HE,Kabir ZN,Forsell Y,et al.Low birth weight in offspring of women with depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy:results from a population based study in Bangladesh.BMC Public Health,2010,10:1-8.

25 Hosseini SM,Biglan MW,Cynthia L,et al.Trait anxiety in pregnant women predicts offspring birth outcomes.Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol,2010,23:557-566.

26 蒋晓敏,陶芳标,董娟,等.孕妇心理健康状况与低出生体重儿关系.中国公共卫生,2009,25:438-440.

27 Al-Dabbagh SA,Al-Taee WY.Risk factors for pre-term birth in Iraq:a case-control study.BMC Pregnancy Childbirth,2006,6:13.

28 Dayan J,Creveuil C,Marks MN,et al.Prenatal depression,prenatal anxiety,and spontaneous preterm birth:a prospective cohort study among women with early and regular care.Psychosom Med,2006,68:938-946.

29 Berle JO,Mykletun A,Daltveit AK,et al.Neonatal outcomes in offspring of women with anxiety and depression during pregnancy.A linkage study from The Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT) and Medical Birth Registry of Norway.Arch Womens Ment Health,2005,8:181-189.

30 Andersson  I,Wulff M,et al.Neonatal outcome following maternal antenatal depression and anxiety:a population-based study.Am J Epidemiol,2004,159:872-881.

I,Wulff M,et al.Neonatal outcome following maternal antenatal depression and anxiety:a population-based study.Am J Epidemiol,2004,159:872-881.

31 Loomans EM,van Dijk AE,Vrijkotte TG,et al.Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is related to adverse birth outcomes:results from a large multi-ethnic community-based birth cohort.Eur J Public Health,2013,23:485-491.

32 Fleuriet KJ,Sunil TS.Reproductive habitus,psychosocial health,and birth weight variation in Mexican immigrant and Mexican American women in south Texas.Soc Sci Med,2015,138:102-109.

33 Rauchfuss M,Maier B.Biopsychosocial predictors of preterm delivery.J Perinat Med,2011,39:515-521.

34 Ghosh JK,Wilhelm MH,Dunkel-Schetter C,et al.Paternal support and preterm birth,and the moderation of effects of chronic stress:a study in Los Angeles county mothers.Arch Womens Ment Health,2010,13:327-338.

35 Kramer MS,Lydon J,Seguin L,et al.Stress pathways to spontaneous preterm birth:the role of stressors,psychological distress,and stress hormones.Am J Epidemiol,2009,169:1319-1326.

36 Orr ST,Reiter JP,Blazer DG,et al.Maternal prenatal pregnancy-related anxiety and spontaneous preterm birth in Baltimore,Maryland.Psychosom Med,2007,69:566-570.

37 Mancuso RA,Schetter CD,Rini CM,et al.Maternal prenatal anxiety and corticotropin-releasing hormone associated with timing of delivery.Psychosom Med,2004,66:762-769.

38 Dole N,Savitz DA,Siega-Riz AM,et al.Psychosocial factors and preterm birth among African American and White women in central North Carolina.Am J Public Health,2004,94:1358-1365.

39 Dole N,Savitz DA,Hertz-Picciotto I,et al.Maternal stress and preterm birth.Am J Epidemiol,2003,157:14-24.

40 Huizink AC,Mulder EJ,Robles de Medina PG,et al.Is pregnancy anxiety a distinctive syndrome?.Early Hum Dev,2004,79:81-91.

41 Matthey S,Ross-Hamid C.The validity of DSM symptoms for depression and anxiety disorders during pregnancy.J Affect Disord,2011,133:546-552.

(收稿日期:2020-02-25)