抑郁症是女性常见的精神疾病。有研究表明,在中国老年人群中,女性抑郁症患病率远高于男性[1],40%中国女性在怀孕期间有过抑郁状态[2]。在全球范围内,女性抑郁症平均伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)高于同年龄段男性,且育龄期女性高于老年女性和幼年女性[3]。抑郁症患者的健康相关生活质量显著低于一般人群[4],因此在育龄期女性人群中开展抑郁症防治将有利于提高其生活质量。本研究基于2019全球疾病负担研究(global burden of disease study 2019,GBD 2019),比较1990—2015年间中国15~49岁育龄期女性人群抑郁症发病、患病和伤残损失寿命年的构成情况,并使用灰色模型GM(1,1)对2025年和2030年该年龄段人群抑郁症发病率、患病率和伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)进行预测,从而为今后开展妇女保健工作提供科学依据。

资料与方法

一、资料来源

数据来源于GBD 2019发布的1990—2019年中国15~49岁女性人群抑郁症发病、患病和伤残损失寿命年资料[5]。疾病类别以GBD 2019提供的分类方法为准,即抑郁症包括抑郁发作(ICD-10:F32)、复发性抑郁(ICD-10:F33)和恶劣心境(ICD-10:F34.1),其中抑郁发作和复发性抑郁被GBD 2019合并为一组统计[6-7]。

二、方法

灰色系统理论被广泛应用于各个学科领域,用以构建含有若干未知参数的模型,其中最常用的是GM(1,1)模型[8]。拟合时,首先需要构建原始序列:X(0)={x(0)(t),t=1,2,…,n},并通过累加生成新的序列:X(1)={x(1)(t),t=1,2,…,n},其中![]() 等式如下:dx(1)(t)/dt+ax(1)(t)=u,其中α与u是待定参数,可以用最小二乘法估计,即:

等式如下:dx(1)(t)/dt+ax(1)(t)=u,其中α与u是待定参数,可以用最小二乘法估计,即:

![]() 基于以上公式,可以得到预测序列:Xp(0)={(e-a-1)[x(0)(1)-u/a]e-at,t=1,2,…,n}[9]。通过计算残差方差与原始数据方差之间的比值c来评估模型预测的精度。当c≤0.35时,说明拟合效果很好,当0.35

基于以上公式,可以得到预测序列:Xp(0)={(e-a-1)[x(0)(1)-u/a]e-at,t=1,2,…,n}[9]。通过计算残差方差与原始数据方差之间的比值c来评估模型预测的精度。当c≤0.35时,说明拟合效果很好,当0.35

结 果

一、发病、患病和伤残损失寿命年分布情况比较

2015年15~49岁女性人群抑郁症发病率、患病率和伤残损失寿命年分别为3 193.62/10万,3 866.72/10万和597.91年(每十万人口),与1990年(发病率:4 703.59/10万;患病率:4 596.74/10万;伤残损失寿命年:每十万人口785.12年)相比均有所下降。图1可知,1990—2015年间,在多数年龄组中,恶劣心境发病人数、患病人数和伤残损失寿命年数在抑郁症发病人数、患病人数和伤残损失寿命年数中所占比例随着时间推移呈波动上升,在25岁以下人群中,以上三个指标的上升趋势更明显;通过年龄组间比较发现,在多数情况下,年龄相对较小的组,恶劣心境发病人数、患病人数和伤残损失寿命年数在抑郁症发病人数、患病人数和伤残损失寿命年数中所占比例也相对较小。

(a) The percentage of new cases of dysthymia relative to new cases of all kinds of depressive disorders; (b) The percentage of total cases of dysthymia relative to total cases of all kinds of depressive disorders; (c) The percentage of years lived with disability due to dysthymia relative to those due to all kinds of depressive disorders

图1 1990—2015年恶劣心境在抑郁症中占比情况

Figure 1 The percentage of new and total cases as well as burdens of dysthymia of relative to all kinds of the depressive disorders from 1990 to 2015

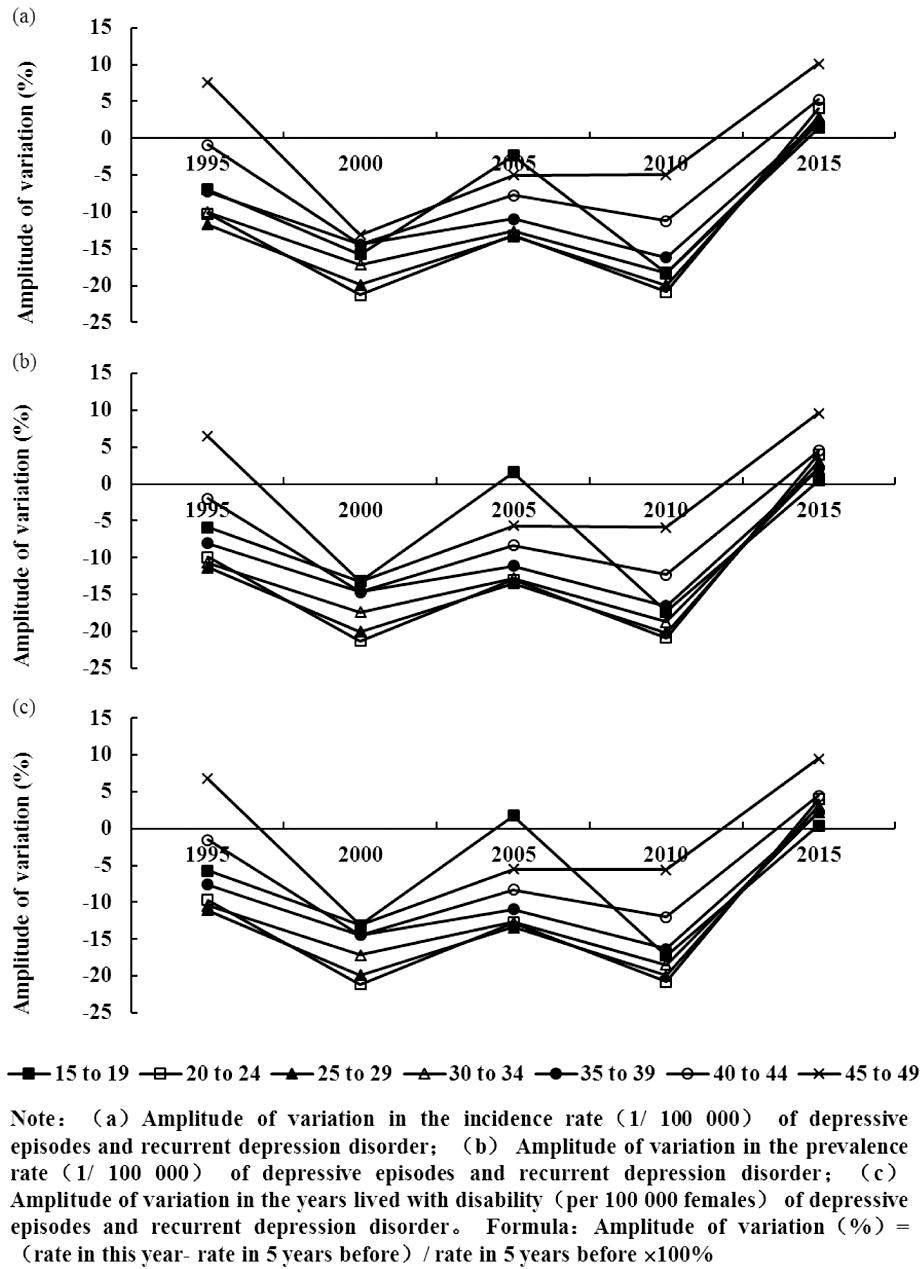

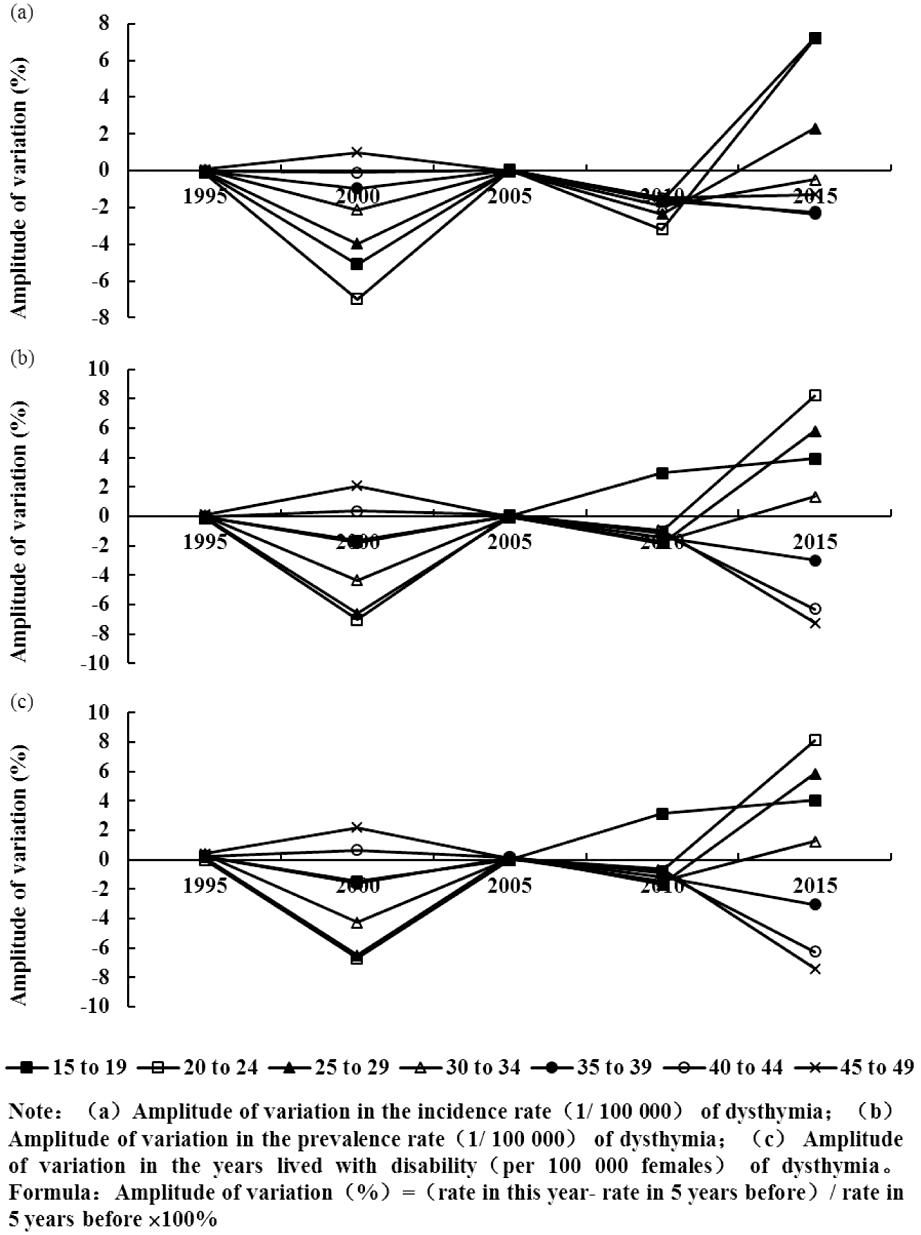

由图2、图3可知,与上一个五年相比,抑郁发作和复发性抑郁的发病率、患病率和伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)变化幅度较大,其中2000年和2010年各年龄组均有不同程度下降;恶劣心境的发病率、患病率和伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)较为稳定,其中2000年和2015年三者的变化相对明显,但均未超过±10%。

图2 1995—2015年抑郁发作和复发性抑郁分布变化情况

Figure 2 Variation of the distribution of depressive episodes and recurrent depression disorder from 1995 to 2015

图3 1995—2015年恶劣心境分布变化情况

Figure 3 Variation of the distribution of dysthymia from 1995 to 2015

二、发病率、患病率和伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)预测

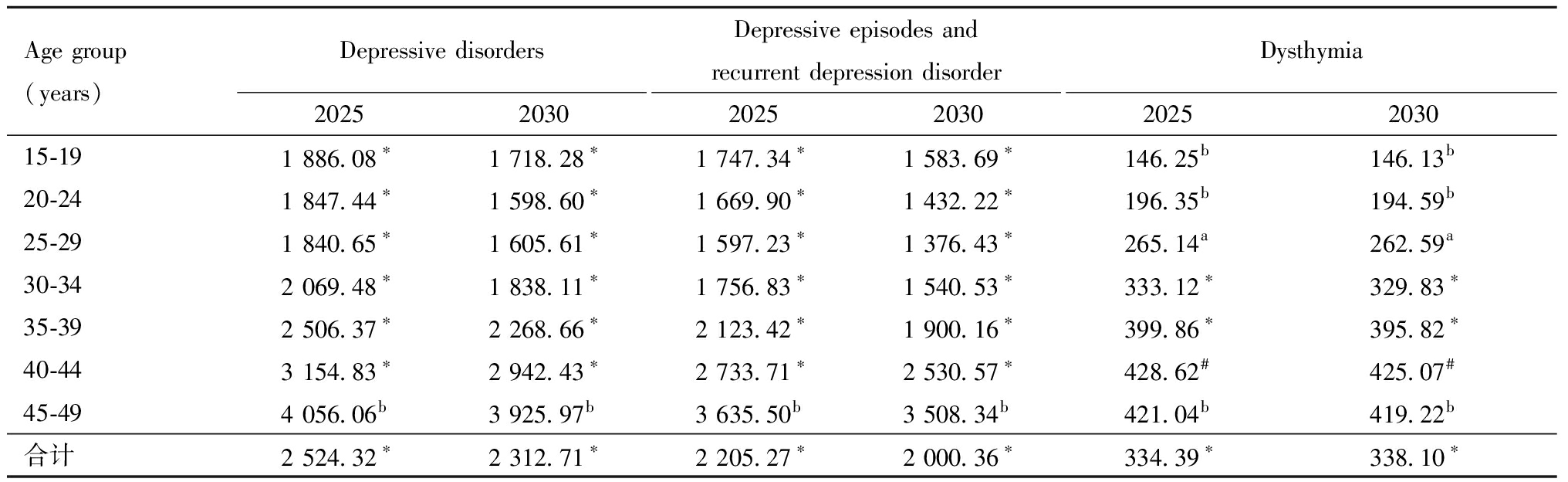

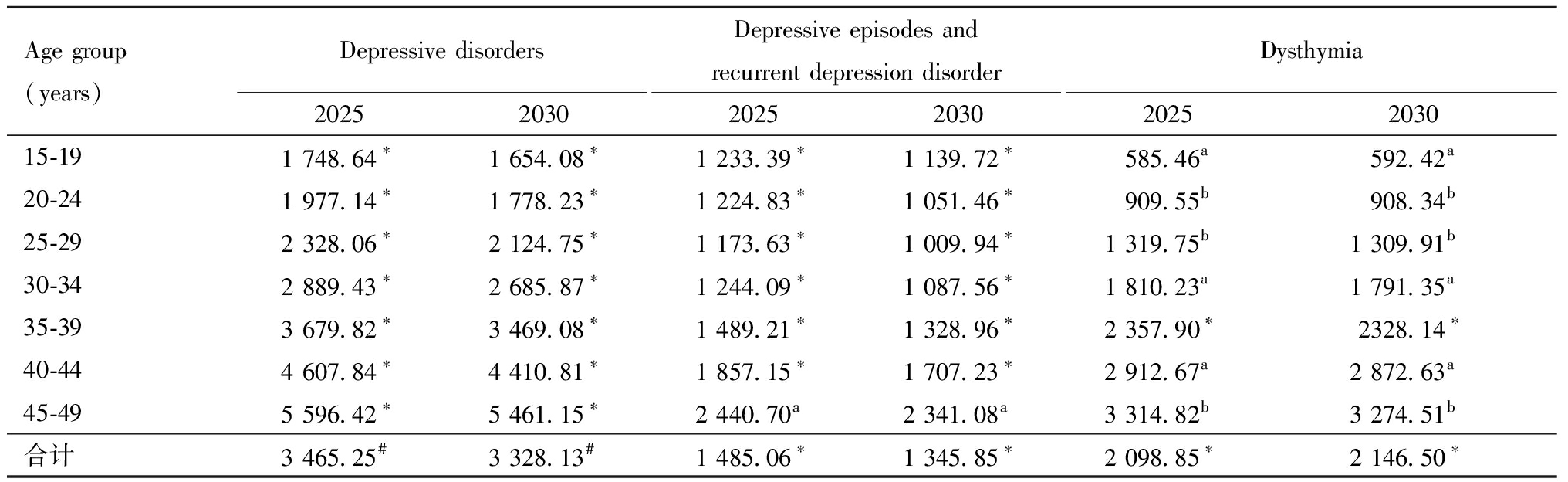

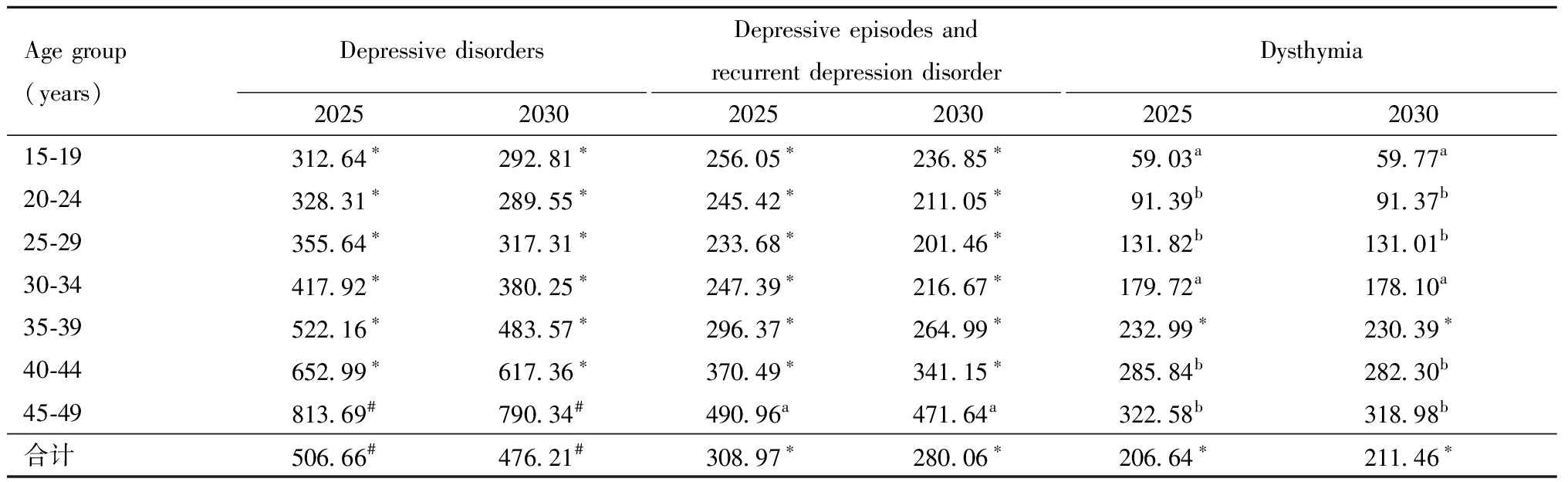

表1~表3分别显示GM(1,1)模型对15~49岁女性抑郁症发病率、患病率和伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)的预测结果。预计至2025年,中国育龄期女性抑郁症平均发病率、患病率和伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)分别为2 524.32/10万、3 465.25/10万和506.66/10万,其中抑郁发作和复发性抑郁分别为2 205.27/10万、1 485.06/10万和308.97年/10万,恶劣心境分别为334.39/10万、2 098.85/10万和206.64年/10万,各年龄组恶劣心境的发病率明显低于抑郁发作和复发性抑郁,但两者的患病率和伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)相差较小,在25岁以上人群中,恶劣心境的患病率甚至超过抑郁发作和复发性抑郁。年龄相对较大组,各类抑郁症的发病率、患病率和伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)也相对较大,40岁以上女性的预测值均超过同期育龄期女性的平均水平。与2025年相比,2030年多数年龄组各类抑郁症的发病率、患病率和伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)会出现不同程度的下降,相较而言,恶劣心境的下降幅度最不明显,部分年龄组甚至出现上升。

表1 15~49岁女性抑郁症发病率(1/10万)预测情况

Table 1 Forecasted incidence rate (1/100 000) of depressive disorders in females aged 15-49 years

Age group(years)Depressive disorders20252030Depressive episodes and recurrent depression disorder20252030Dysthymia2025203015-191 886.08∗1 718.28∗1 747.34∗1 583.69∗146.25b146.13b20-241 847.44∗1 598.60∗1 669.90∗1 432.22∗196.35b194.59b25-291 840.65∗1 605.61∗1 597.23∗1 376.43∗265.14a262.59a30-342 069.48∗1 838.11∗1 756.83∗1 540.53∗333.12∗329.83∗35-392 506.37∗2 268.66∗2 123.42∗1 900.16∗399.86∗395.82∗40-443 154.83∗2 942.43∗2 733.71∗2 530.57∗428.62#425.07#45-494 056.06b3 925.97b3 635.50b3 508.34b421.04b419.22b合计2 524.32∗2 312.71∗2 205.27∗2 000.36∗334.39∗338.10∗

Note:*C≤0.35,the fitting performance is excellent;#0.35

表2 15~49岁女性抑郁症患病率(1/10万)预测情况

Table 2 Forecasted prevalence (1/100 000) of depressive disorders in females aged 15-49 years

Age group(years)Depressive disorders20252030Depressive episodes and recurrent depression disorder20252030Dysthymia2025203015-191 748.64∗1 654.08∗1 233.39∗1 139.72∗585.46a592.42a20-241 977.14∗1 778.23∗1 224.83∗1 051.46∗909.55b908.34b25-292 328.06∗2 124.75∗1 173.63∗1 009.94∗1 319.75b1 309.91b30-342 889.43∗2 685.87∗1 244.09∗1 087.56∗1 810.23a1 791.35a35-393 679.82∗3 469.08∗1 489.21∗1 328.96∗2 357.90∗2328.14∗40-444 607.84∗4 410.81∗1 857.15∗1 707.23∗2 912.67a2 872.63a45-495 596.42∗5 461.15∗2 440.70a2 341.08a3 314.82b3 274.51b合计3 465.25#3 328.13#1 485.06∗1 345.85∗2 098.85∗2 146.50∗

Note:*C≤0.35,the fitting performance is excellent;#0.35

表3 15~49岁女性抑郁症伤残损失寿命年(每十万人口)预测情况

Table 3 Forecasted years lived with disability (per 100 000 females) of depressive disorders in females aged 15-49 years

Age group(years)Depressive disorders20252030Depressive episodes and recurrent depression disorder20252030Dysthymia2025203015-19312.64∗292.81∗256.05∗236.85∗59.03a59.77a20-24328.31∗289.55∗245.42∗211.05∗91.39b91.37b25-29355.64∗317.31∗233.68∗201.46∗131.82b131.01b30-34417.92∗380.25∗247.39∗216.67∗179.72a178.10a35-39522.16∗483.57∗296.37∗264.99∗232.99∗230.39∗40-44652.99∗617.36∗370.49∗341.15∗285.84b282.30b45-49813.69#790.34#490.96a471.64a322.58b318.98b合计506.66#476.21#308.97∗280.06∗206.64∗211.46∗

Note:*C≤0.35,the fitting performance is excellent;#0.35

讨 论

据GBD 2019发布的数据显示,2015年全球15~49岁女性抑郁症平均发病率为5 417.85/10万,患病率为5 148.47/10万,高于中国平均水平(发病率:3 193.62/10万,患病率:3 866.72/10万),但中国的恶劣心境发病率(327.99/10万)与患病率(1 999.78/10万)超过了同期全球平均值(发病率:304.61/10万,患病率:1 808.54/10万)[5],该现况提示未来需进一步推进育龄期女性恶劣心境的预防与干预工作。本研究发现,15~19岁女性抑郁症发病率预测值高于20~24岁和25~29岁女性,这可能与15~19岁女性正经历着学业压力最大的高中时期有关,在30岁以上女性中,抑郁症发病率预测值随年龄增大而增加,其中40~49岁女性抑郁症的发病情况超过育龄期女性的平均水平,这可能与其步入更年期后内分泌发生变化有关。据本研究预测,2025和2030年,中国15~49岁女性抑郁症患病率随着年龄的增长而增加,自25岁起,恶劣心境患病率超过抑郁发作和复发性抑郁,成为抑郁症患病率的主要构成,该结果提示未来对女性心理保健工作的投入应根据年龄和病种特点进行合理分配,更加重视对恶劣心境的防治。本研究结果显示,15~19岁女性恶劣心境的患病率和伤残损失寿命年可能在未来几年内出现上升,这与其他年龄组及其他病种的变化趋势相反,这种以慢性抑郁情绪为主要症状的疾病可能与青春期激素变化、负性生活事件(如:结交不良同伴、人际关系变动)等因素有关[11],未来应进一步重视青少年时期的心理健康教育,提升青少年的情绪调节能力。

负性生活事件(如:受伤和生病、失业、工资减少)是抑郁症的重要危险因素之一[12],以往研究发现,在灾难事件中经历过恐惧的人群,抑郁症发生风险显著较高[13],在创伤后情绪调节困难者更容易出现抑郁症状[14]。职业紧张也会增加抑郁症的发病风险,如:工作负荷量大、日均工作时间长、工作满意度低、角色冲突和角色模糊[15-17]。除了以上外部风险因素外,抑郁症的内部风险因素包括神经质、外向性、依赖性、自我批评等人格特质[18-20]。目前,已有专用于产后抑郁症易感人格测量的评估量表(vulnerable personality style questionnaire,VPSQ)[21]和用于抑郁型人格测量的评估量表(depressive personality disorder inventory,DPDI)[22],这类测量工具的临床应用将有利于育龄期女性抑郁症易感性的早期识别。

抑郁症对于女性健康有多种不良后果。有研究者发现,存在抑郁症状的孕妇,其患进食障碍的风险高于无症状者[23],抑郁水平也是进食障碍患者治疗效果的重要预测因素之一[24];产前抑郁症状是孕期睡眠质量的重要不利因素[25],抑郁的孕妇在夜间醒来的次数更多,并且在夜间花更多的时间试图入睡[26];围绝经期抑郁症患者的社会适应水平明显低于非抑郁症者[27],且抑郁症与自杀企图之间可能存在相同的遗传背景[28];为缓解抑郁等不良情绪,部分女性还会采取非自杀式自伤行为[29]。

为降低抑郁症对育龄期女性的不利影响,可以采用正念认知疗法进行干预,即采用接纳的心态应对当下的身心体验、感受,不评价地保持觉知,不回避自己的真实感受,有研究表明,正念疗法可以有效降低重度抑郁的发作天数,并可获得良好的卫生经济效益[30],对于轻度抑郁症患者,正念疗法也表现出明显的积极效应[31]。以病人为中心的护理也是缓解女性抑郁情绪的有效手段,通过征求患者对护理的偏好以及对相关问题的担忧,进而制定个性化诊疗方案,以提高患者满意度、改善抑郁结果[32]。另外,还应关注育龄期女性抑郁症的风险因素,宣传动员经历过负性生活事件、职业紧张程度高、具有高抑郁易感度人格特质的女性接受心理咨询,探究其不良情绪的根源,帮助其建立起积极的认知体系,从而降低抑郁症的发生风险。

1 Zhang YS,Jin Y,Rao WW,et al.Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of major depressive disorder in older adults in Hebei province,China.J Affect Disord,2020,265:590-594.

2 Li J,Mao J,Du Y,et al.Health-related quality of life among pregnant women with and without depression in Hubei,China.Matern Child Health J,2012,16:1355-1363.

3 Ferrari AJ,Charlson FJ,Norman RE,et al.Burden of depressive disorders by country,sex,age,and year:findings from the global burden of disease study 2010.PLoS Med,2013,10:e1001547.

4 Riihimäki K,Sintonen H,Vuorilehto M,et al.Health-related quality of life of primary care patients with depressive disorders.Eur Psychiatry,2016,37:28-34.

5 Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network.Global burden of disease study 2019 (GBD 2019) results.Seattle,United States:Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME),2020.https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/

6 Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network.Codebook.10-15-2020.http://ghdx.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/ihme_query_tool/IHME_GBD_2019_CODEBOOK.zip.

7 Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network.Global burden of disease study 2019 (GBD 2019) cause list mapped to ICD codes.http://ghdx.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/record-attached-files/IHME_GBD_2019_CAUSE_ICD_CODE_MAP_Y2020M10D15.XLSX

8 Lin Y,Liu SF.A historical introduction to grey systems theory.2004 IEEE international conference on systems,man and cybernetics (IEEE Cat.No.04CH37583),The Hague,Netherlands,2004:2403-2408.

9 邓聚龙.灰色系统基本方法.北京:工学院出版社,1987.

10 孔超,刘元凤,沈续雷.灰色预测模型的SAS程序改进.中国卫生统计,2008,25:640-641.

11 侯金芹,陈祉妍.青少年抑郁情绪的发展轨迹:界定亚群组及其影响因素.心理学报,2016,48:957-968.

12 Russell DW,Clavél FD,Cutrona CE,et al.Neighborhood racial discrimination and the development of major depression.J Abnorm Psychol,2018,127:150-159.

13 Guo J,He H,Qu Z,et al.Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among adult survivors 8 years after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China.J Affect Disord,2017,210:27-34.

14 Chang C,Kaczkurkin AN,McLean CP,et al.Emotion regulation is associated with PTSD and depression among female adolescent survivors of childhood sexual abuse.Psychol Trauma,2018,10:319-326.

15 Yoshizawa K,Sugawara N,Yasui-Furukori N,et al.Relationship between occupational stress and depression among psychiatric nurses in Japan.Arch Environ Occup Health,2016,71:10-15.

16 Song KW,Choi WS,Jee HJ,et al.Correlation of occupational stress with depression,anxiety,and sleep in Korean dentists:cross-sectional study.BMC Psychiatry,2017,17:398.

17 Nakada A,Iwasaki S,Kanchika M,et al.Relationship between depressive symptoms and perceived individual level occupational stress among Japanese schoolteachers.Ind Health,2016,54:396-402.

18 Kendler KS,Neale MC,Kessler RC,et al.A longitudinal twin study of personality and major depression in women.Arch Gen Psychiatry,1993,50:853-862.

19 Enns MW,Cox BJ.Personality dimensions and depression:review and commentary.Can J Psychiatry,1997,42:274-284.

20 Koorevaar A,Hegeman JM,Lamers F,et al.Big Five personality characteristics are associated with depression subtypes and symptom dimensions of depression in older adults.Int J Geriatr Psychiatry,2017,32:e132-e140.

21 Boyce P,Hickey A,Gilchrist J,et al.The development of a brief personality scale to measure vulnerability to postnatal depression.Arch Women Ment Hlth,2001,3:147-153.

22 Huprich SK,Margrett J,Barthelemy KJ,et al.The depressive personality disorder inventory:an initial examination of its psychometric properties.J Clin Psychol,1996,52:153-159.

23 Santos A,Benute G,Santos N,et al.Presence of eating disorders and its relationship to anxiety and depression in pregnant women.Midwifery,2017,51:12-15.

24 Fewell LK,Levinson CA,Stark L.Depression,worry,and psychosocial functioning predict eating disorder treatment outcomes in a residential and partial hospitalization setting.Eat Weight Disord,2017,22:291-301.

25 Yang Y,Mao J,Ye Z,et al.Determinants of sleep quality among pregnant women in China:a cross-sectional survey.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med,2018,31:2980-2985.

26 Ruiz-Robledillo N,Canário C,Dias CC,et al.Sleep during the third trimester of pregnancy:the role of depression and anxiety.Psychol Health Med,2015,20:927-932.

27 Wariso BA,Guerrieri GM,Thompson K,et al.Depression during the menopause transition:impact on quality of life,social adjustment,and disability.Arch Womens Ment Health,2017,20:273-282.

28 Thornton LM,Welch E,Munn-Chernoff MA,et al.Anorexia nervosa,major depression,and suicide attempts:shared genetic factors.Suicide Life Threat Behav,2016,46:525-534.

29 Power J,Brown SL,Usher AM.Non-suicidal self-injury in women offenders:motivations,emotions,and precipitating events.Int J Forensic Ment,2013,12:192-204.

30 Shawyer F,Enticott JC,Ozmen M,et al.Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the management and prevention of depression.Aust Nz J Psychiat,2016,50:1001-1013.

31 Xu XP,Zhu XW,Liu QQ.Can self-training in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy alleviate mild depression among Chinese adolescents.Soc Behav Personal,2019,47:UNSP e7944.

32 Rossom RC,Solberg LI,Vazquez-Benitez G,et al.The effects of patient-centered depression care on patient satisfaction and depression remission.Fam Pract,2016,33:649-655.